The State of Pediatric Autism Diagnosis in the U.S.: Gridlocks, Inequities and Missed Opportunities Persist

A new analysis of specialty centers across the U.S. confirms that families concerned about their child’s development and behavioral health face unacceptably long wait times, unnecessarily complex and highly variable processes, and reimbursement barriers and inequities – all adding up to delayed diagnosis and missed opportunities for life-changing early intervention for children.

A new analysis of specialty centers across the U.S. confirms that families concerned about their child’s development and behavioral health face unacceptably long wait times, unnecessarily complex and highly variable processes, and reimbursement barriers and inequities – all adding up to delayed diagnosis and missed opportunities for life-changing early intervention for children.

An analysis of 111 specialty centers in the U.S. confirms the crisis of care for children and families seeking a diagnosis of developmental delays and autism evaluation. The delays in diagnosis revealed by this survey demonstrate why many children with autism, and other developmental/behavioral conditions, are missing a critical early intervention period when significant, positive impacts on neurological development can be made. This report of the survey’s key findings sheds light on the inequities and inefficiencies in the system that are leaving many children and families behind. The survey was designed and conducted by Scott Badesch, Former President of the Autism Society of America, and sponsored by Cognoa.

Multiple factors cause delays

The analysis uncovers several issues with the current processes for autism diagnosis, including:

- Unacceptably long wait times for evaluations

- Specialist shortages

- Lengthy, labor and time intensive evaluations that are unnecessary for many children

- Heavy documentation burden for healthcare providers

- No standard of care for diagnostic processes

- Disparities in access due to limited and variable reimbursement and coverage

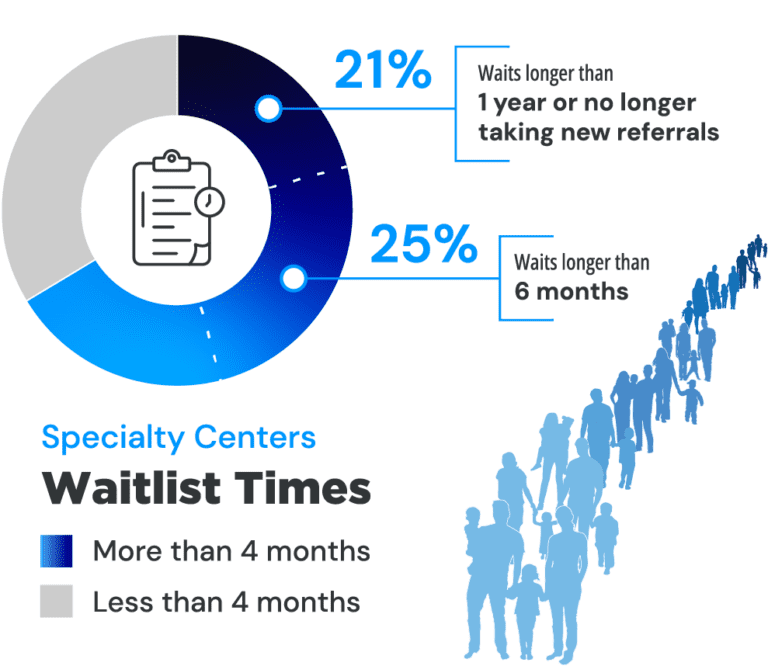

Families wait months or more for answers

Wait times for autism diagnosis are unacceptably long for many children across the U.S. Nearly two-thirds of specialty centers that conduct autism evaluations (61%) had wait times longer than 4 months. Of that group, 25% reported waitlists of more than half a year. 21% reported waitlists of more than a year or had waitlists that were so full that they were no longer taking new referrals. “Imagine your child is showing signs of autism, and imagine you are told your child cannot be diagnosed nor access therapies that would help your child for at least two years,” said Scott Badesch, Former President of the Autism Society of America. “Families of minority backgrounds, low income, and/or in rural areas often don’t have any opportunities for early diagnosis and services. A person who suspects he or she has cancer, can and should get diagnosed within days. But if your child shows signs of autism, the wait time is months to years. This is not acceptable.”

A recent poll at the Society for Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics Annual Meeting in September 2023 showed even longer wait lists. More than half of the audience of developmental behavioral pediatricians of academic or hospital affiliated centers self-reported waitlists of longer than 9 months.

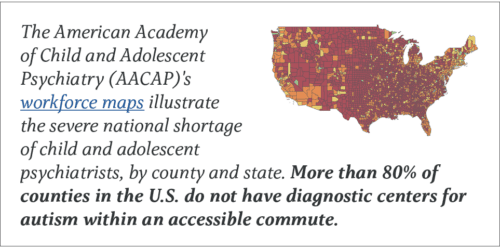

Not enough specialists for the number of children in need

The volume of children needing evaluation exceeds the limited number of specialists who complete them. More than two-thirds of centers (69%) report shortages in their workforce. 61% percent of centers also report that volume of children referred to them is a barrier to making evaluations in a reasonable time frame.

* AAP

** 20% of CAPs are above age 70

*** AACAP

“We also take over one thousand calls from the community every year, and the most common request is for autism assessments.” – survey respondent

“Primary care clinicians, specifically pediatricians, who are equipped with a diagnostic that is made for their setting can accurately and rapidly evaluate, diagnose, and manage most children with developmental delays and autism – all from within the medical home,” said Dr. Sharief Taraman, CEO of Cognoa, Past President of the American Academy of Pediatrics-Orange County Chapter and Board Member of the American Academy of Pediatrics-California, Associate Professor University of California-Irvine School of Medicine. “Yet, in most cases, the forces that be, be it tradition or policy, make the ‘autism specialist’ the only option for a diagnosis. This isn’t working for families, specialists, nor primary care clinicians. This is an imbalance that healthcare leaders and policymakers must take seriously when directing future resources and developing initiatives to standardize, equitize, and streamline evaluation processes for families, irrespective of insurance type. We as a nation are failing our children. It is vital that we expand and empower the pool of providers who can evaluate and diagnose children, and we need to start in primary care.”

“Primary care clinicians, specifically pediatricians, who are equipped with a diagnostic that is made for their setting can accurately and rapidly evaluate, diagnose, and manage most children with developmental delays and autism – all from within the medical home,” said Dr. Sharief Taraman, CEO of Cognoa, Past President of the American Academy of Pediatrics-Orange County Chapter and Board Member of the American Academy of Pediatrics-California, Associate Professor University of California-Irvine School of Medicine. “Yet, in most cases, the forces that be, be it tradition or policy, make the ‘autism specialist’ the only option for a diagnosis. This isn’t working for families, specialists, nor primary care clinicians. This is an imbalance that healthcare leaders and policymakers must take seriously when directing future resources and developing initiatives to standardize, equitize, and streamline evaluation processes for families, irrespective of insurance type. We as a nation are failing our children. It is vital that we expand and empower the pool of providers who can evaluate and diagnose children, and we need to start in primary care.”

“It is vital that we expand and empower the pool of providers

who can evaluate and diagnose children, and we need to start

with primary care providers.”

– Sharief Taraman, CEO of Cognoa

The urgent need to engage the broader primary care workforce in the process of autism diagnosis is also recognized by the leadership of the American Academy of Pediatrics. Amongst AAP’s most recent top leadership resolutions is their commitment to take action to ensure a diagnosis of autism by pediatricians “allows the coverage of appropriate services by both private insurers and state Medicaid programs.”

Unnecessarily complicated & time-consuming processes

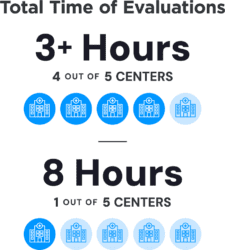

Another obstacle that limits access to a timely diagnosis is the lengthy evaluations that are routinely given irrespective of the complexity of their presentation. Multidisciplinary team assessments have created barriers because they are time-intensive, specialist dependent, hard to access, and expensive. In more than 4 out of 5 centers (83%), evaluations take more than three hours. One of every four specialty centers report that their evaluations can take 8 hours.

Another obstacle that limits access to a timely diagnosis is the lengthy evaluations that are routinely given irrespective of the complexity of their presentation. Multidisciplinary team assessments have created barriers because they are time-intensive, specialist dependent, hard to access, and expensive. In more than 4 out of 5 centers (83%), evaluations take more than three hours. One of every four specialty centers report that their evaluations can take 8 hours.

“Wait times, prolonged report writing time, and efficiency in the intake process are all real challenges in the diagnosis of children and adults with autism,” said another clinician in the survey. “A number of these challenges are perpetuated by professionals who continue to provide extensive evaluations that often duplicate those that have been completed within the school system and early intervention programs.”

Another clinician pointed out that the documentation requirements of autism assessment is a barrier for families: “The ability to complete all the documentation varies from family to family, and depends on their ability to complete forms, respond to calls, provide transportation, and be flexible with scheduling. Unfortunately, many families are not able to complete all the items needed.”

Barriers to reimbursement shut out the already disadvantaged

“Insurance companies create barriers to diagnosing efficiently,” said one provider in the survey. “One way they do this is by mandating specific measures that have known biases and disparities.”

Families struggle to find ways to pay for lengthy autism assessments. The healthcare providers who provide developmental and autism assessments are not always covered by a family’s medical insurance. In these cases, families must either pay out of pocket and/or travel long distances.

Families struggle to find ways to pay for lengthy autism assessments. The healthcare providers who provide developmental and autism assessments are not always covered by a family’s medical insurance. In these cases, families must either pay out of pocket and/or travel long distances.

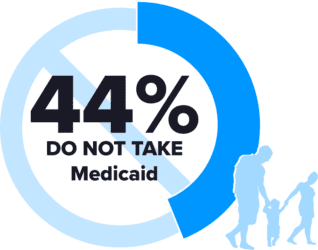

Disadvantaged families are affected the most, as 44% of centers surveyed do not take Medicaid, forcing families to find other ways to pay or forego assessment. Meanwhile, only 65% of practices take commercial insurance, so if families cannot pay costs out of pocket up front, there is a high likelihood they will be left behind altogether.

“Only families that can afford to pay out of pocket can access our practice.”

– survey respondent

“The barriers to accepting health insurance are a real issue,” said a clinician in the survey. “Extremely low reimbursement rates from insurance means we cannot afford to accept insurance at this time. We are private pay as a result, which means that only families that can afford to pay out of pocket can access our practice. And for those who cannot afford it, wait times are much longer for practices that accept insurance or Medicaid.”

Another specialist summarized the burden that inadequate reimbursement has on the practice, saying, “Honestly, it just doesn’t pay well enough to justify my time at the amount and intensity necessary (to build a helpful report that will unlock services).”

There is no “standard of care”

Another factor that causes inequities and complications in autism diagnosis in the U.S. is that there is not a single standard of care universally used to evaluate children with suspected developmental delay or signs of autism. There are well documented state-to-state and payor-to-payor differences in requirements for an autism diagnosis to be recognized and reimbursed. These include differences in the type of provider approved to conduct the evaluation and the specific tests required. Among specialty center providers across the country, more than 30 different tools are variously used to assess patients. The wide range of evaluative tools used may contribute to inequities in results and outcomes for patients from center to center.

Change is necessary, and possible

With so many systemic and financial barriers to diagnosis and care, not only are children missing out on potentially life-changing early interventions, but families are faced with long wait times while their worries about their children go unanswered, often as long as years. Families are not only impacted in terms of care, but also financially, as they must balance the dual challenge of the high cost of care and the potential for considerable missed work time and income, as they attempt to navigate a complex, fragmented, and inequitable system.

“Advocates would do well to support policies that encourage providers to get out of their own way,” said one specialist in the survey. “We need to prioritize the needs of their local populations by adopting innovative solutions which include comprehensive integration of APPs (advanced practice providers), general pediatricians with additional training, and other mental health workers, especially when these services are provided within a patient’s medical home in an integrated model. To be clear, this can be done in a cost-effective manner that’s good for morale and improves providers personal satisfaction—especially if the work is done in a way that clearly advances goals related to diversity and equity.”

Given the barriers to timely evaluation and care underscored by this analysis, there is an urgent need for policies to support the reimbursement and access pathways of available FDA regulated diagnostics that, with a whole child data-driven design, equip more providers to evaluate, diagnose, and manage children within primary care.

About the costly delay in diagnosis in the U.S.

In the U.S., as many as 25% of children are at risk for a developmental delay, and autism is estimated to affect 1 in 36 children. Autism can be reliably diagnosed in children as young as 18 months, yet the average age of diagnosis has remained stagnant for decades at over 4 years of age. Non-white children, females, and those from rural areas or disadvantaged socio-economic backgrounds are often diagnosed even later or missed altogether. Early interventions improve lifelong outcomes for children, whereas lack of or delayed treatment increases the likelihood of lifetime, comorbid mental health conditions. All-cause medical costs are approximately double for children who experience a longer time to diagnosis compared with a shorter time to diagnosis.

About the analysis: survey methodology

Both multi- and sole practitioner specialty centers – including hospitals, private practices, public health clinics, government agencies, and academic entities – conducting autism evaluations were identified through a combination of web searches and claims data analysis. A brief anonymous, online survey was distributed to identified autism specialty centers across all U.S. states and the District of Columbia (n=1,004) via email. Responses were collected November 2022 through March 2023. The study received an IRB exemption from Advarra (Pro00067552). Of 111 specialty centers, 61.76% were multi-practitioner diagnostic centers. The remaining 38.24% were sole practitioner centers. Responses were received from 38 unique states. Highest responses were received from CO (9%); MA (6%); PA, UT, TX, CA (all 5%), AZ, OH and VA (all 4%), NJ, RI, MS, NY, TN (all 3%).